Industry analyst Michael Gubbins explains why the discussion about the future of film needs to be far more cohesive…

‘An exciting vision of a coherent, joined-up film industry.’ That was the spin from communication, culture and creative industries minister Ed Vaizey when announcing the British Film Institute’s takeover of the UK Film Council’s functions. The irony won’t be lost on anyone who recalls that the UK Film Council was itself set up with pretty much that same mission, of creating a united film industry with a sustainable business model.

We’ll skip over the doubts that there was a cunning rationale for a rushed decision with minimal consultation and take the idea of sustainability at face value. That takes us right back to the indie movie business alchemy of trying to turn a collection of specialised small- and medium-sized businesses into a coherent industry. Back in 2002, the then UK Film Council chairman Alan Parker put it perfectly: ‘We are not one film industry, but many industries’. It was one of those ‘emperor’s new clothes’ observations that ought to be at the top of every letter and email sent to policymakers.

Yet what Parker was talking about was a set of industries that, for all the divergence, still added up to something that worked, after a fashion. There may have been a huge and unacceptable gulf between Hollywood studios and the independent sector, but the end product was still essentially a 35mm print with a DVD later, and the disturbingly large gap between producer and exhibitor still managed, albeit imperfectly, to get film onto the big screen.

That point was reached through decades of bodge and compromise— and often force of personality—rather than evolution. We can point to the holes, of course: the absence of transparency in finance; the lack of recoupment for producers; serious limitations in marketing and distributing independent film; and an exhibition business with little control over content. But let’s not forget that this ragged industrial structure still managed an extraordinary recovery from the doldrums of the mid-1980s.

If the industry is more art than science, it has at least displayed a bloody-minded resilience. And there has always been one unifying characteristic: a love of film itself. From the loftiest exec to the lowliest purveyor of popcorn, there is a sense of being part of something bigger, a shared history. The question is whether that shared sense of purpose can really be enough to get us through the next few turbulent years.

“The issue for film is that it is trying to adapt today’s analogue industries for a digital age.”

It is now clear that the gap that really needs to be addressed is between film and its audience, as our economic scarcity model tries to cope with the demand-driven culture: any time, any place, anywhere. Sit down with a child’s box of Lego and it is easy enough to construct something that looks like a convincing working model for a new industry structure. It will probably be a relatively simple design, with maybe a few bricks to spare. It is highly unlikely to be anything like the existing business.

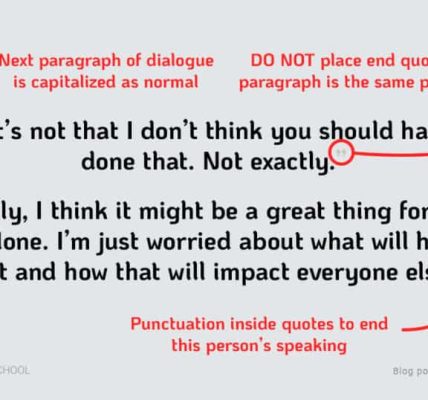

The issue for film is that it is trying to adapt today’s analogue industries for a digital age. Talking to delegates in recent weeks at conferences for writers, producers, distributors and exhibitors, it is clear that each is trying to find plans for change, but the future is being judged by the needs and desires of a specific industry discipline. It is not that the ideas are incoherent, it is that they are incompatible with those of their colleagues in other parts of the business.

Indeed, rather than Lego, the appropriate metaphorical toy is the Rubik’s Cube; it is easy to complete one side, but extremely difficult to coordinate the moving parts to complete the whole. The difficulties in digital cinema, as discussed in movieScope 19, demonstrate the point. In some ways, this should be the easy part of digital change; it is, in essence, an upgrade of cinema equipment, not some digital paradigm shift. And yet at Europa Distribution in Lisbon, and a week later at Europa Cinemas in Paris, it was obvious that digital roll-out has accentuated divides between producer, sales agent, distributor and exhibitor. The eyes aren’t on the prize that comes with D-cinema, but on the pain of transition in the various components of the independent industry.

That’s not true of Hollywood, which has bet a fair bit of the farm on re-equipping cinemas for 3D and to reduce distribution costs. It has a single business strategy based on transparent business objectives, and that singularity means that the studios have been able to retain the domination that indie optimists felt might be under threat. It has not, as some critics claim over issues such as D cinema standards, divided and ruled. The independent industry did the dividing all on its own, and the divisions will be far more exposed in the coming on-demand era, which opens up fundamental questions on the economic model of the industry: territorial rights; the ownership of those rights; release windows; etc. That requires a holistic view of what is in the best interests of film as a whole, rather than the film industry as currently constituted. But where will the necessary leadership come from?

Equally as worrying is that the constituent parts are so small and specialised that effective innovation is all but impossible, at best squeezed into an already overstretched day job. There is a clear role for the public sector here in helping finance innovation, but it too is shackled to the old divisions; funds are specifically allocated to the existing industrial structures and the objectives are clouded. A sustainable industry? A bulwark against Hollywood? Inward investment? It is, for example, too focused on production, funding an unsustainable amount of product (up 27 per cent in Europe in the last 5 years, according to the European Audiovisual Observatory). And it is not focused enough on creating sustainable production businesses. Parker’s speech in 2002 also highlighted the essential truth that cinema is a distribution business.

That is not to say that it is a business about distributors, but one which has to be focused on audiences to work. Only by working back from the audience can you build a real industry.