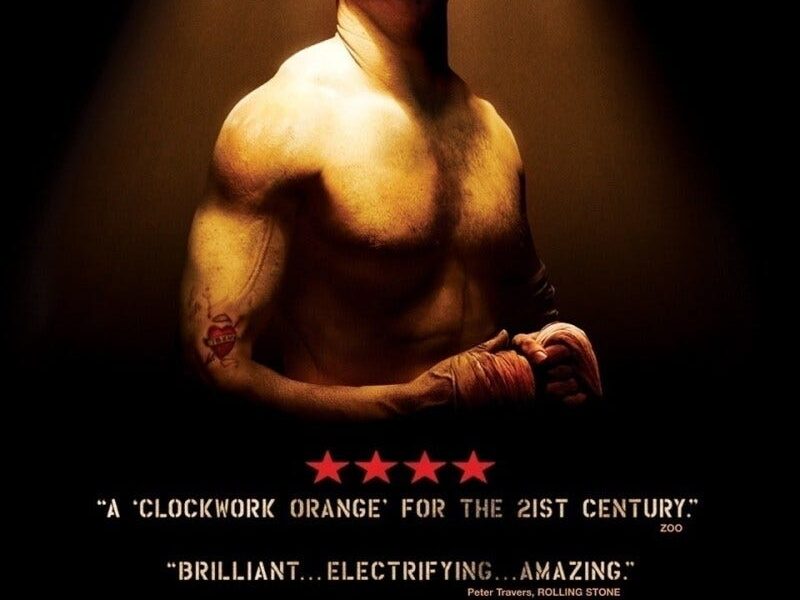

BRONSON – Nicolas Winding Refn: Violence and the Grotesque Medium

Refn followed this with the gritty BLEEDER and then his first English language production, the psychological horror FEAR X, written in collaboration with cult novelist Hubert Selby Jr. While well received, financial problems with FEAR X led to the director declaring himself bankrupt.

He then rejected the idea of making a PUSHER sequel, suggesting instead that he make two PUSHER sequels, each focusing on a different supporting character from the original film. Breaking the familiar pattern of the diminishing creative returns of sequels, PUSHER II and III are considered by many (Refn included) to be better than the original film.

Last year, Refn directed two features back to back. The second of these is VALHALLA RISING, starring Mads Mikkelsen: a sci-fi film set in the Dark Ages (to be released this Autumn). But first is the brutal, theatrical and artistically bold BRONSON (now on release in the UK), about Charles Bronson, “Britain’s most violent prisoner”. Charles Bronson has spent 34 years in prison, 30 of them in solitary confinement, and has had his original sentences for armed robbery lengthened by attacking prison guards and other prisoners and taking an art teacher hostage. But he has also won 11 Koestler Awards for his poetry and art.

“I don’t believe that film makes people violent. However, because film is such a grotesque medium and so wide in its appeal, it can show how violent people react. It shows you how to be violent.”

The release of BRONSON has sparked controversy, with the National Chairman of the Prison Officers’ Association, Colin Moses, calling the film “an absolute disgrace”, accusing it of glorifying Bronson, and Conservative MP David Davies saying that “it’s quite wrong that money is going to be made out of what this man has done”. Others have questioned whether the film should have received any Lottery funding. Most of those who’ve commented about the film haven’t even seen it. Of those who have seen it, the reviews have been markedly mixed, with The Times’ Wendy Ide enthusing that “it eschews the geezer-porn of incorrigible bad lads and glamorised violence [and is] considerably more intelligent and interesting than its subject,” while the Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw found the opposite to be the case: “it seems depressingly geared towards the geezer-porn market [and is] indulgent and unenlightening.”

A writer-director-producer of intense, dark films, Refn tells movieScope that for all the violent films he’s seen (and he’s seen a lot), the most violent was SOPHIE’S CHOICE. He also discusses how the story of BRONSON (the first feature he hasn’t produced) shares a lot with his own life and even that of Hans Christian Andersen.

We meet on the day BRONSON is released in the UK. So how do you feel about some of the reactions this week? It’s been a bit—

A bit?! It’s been insane. But I look at it this way: if everybody likes what you make, there’s something wrong. If everyone hates it, there’s something wrong. Everything I’ve done has always split people very much down the middle. A lot of people who haven’t seen the film have opinions about it, let alone the strong opinions of the people who have seen it. But controversy is very good publicity.

Do you always read the reviews of your films?

Very rarely. I read the ones that like me. The ones that don’t like me, what am I going to do?

Perhaps with the ones that don’t like your film, you might think, later on, that they had an interesting point to make, even if you disagree.

[He laughs]. Well, not really. It’s always nice when somebody likes your work. If somebody doesn’t, then that’s a shame. But I have a very strong belief that art is a very powerful medium. As powerful as an atom bomb, but instead art inspires us to think. And that’s why producing art is something that is still very much part of our lives. It’s very important to humanity.

At the premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring there was a riot.

Yes, they were tearing the place up. The police had to come. That just goes to show that even though we’re controlled, civilised human beings, it doesn’t take a whole lot to freak everybody out. Some things need longer to be absorbed. Jonathan Ross in his review of BRONSON on Film 2009, said something very kind. He was very praising of the craftsmanship, but also said that he didn’t quite know how to feel about the film. My reaction to that is: “Well, thank you very much, Mr. Ross. That’s a very good reaction.”

“When I was young, I wanted to be very famous. In the film, Bronson does ultimately become a famous person, but he then realises it’s not that satisfying. It’s really when he opens himself up to artistic expression that he actually becomes a whole person and Charles Bronson is born.”

Unlike your earlier films, BRONSON wasn’t a project that you initiated yourself. How did it come about?

The producer Rupert Preston, who has distributed all my films in the UK and with whom I have a very good working relationship, had the project and suggested I take a look. I’ve never lived in Britain and I’d no idea who this prisoner Charles Bronson was. The script didn’t get me very excited as the overall character approach was pretty generic. It tried to psychoanalyse Bronson, which I thought was very wrong and didn’t do him justice. In fact, it made him less interesting. I didn’t know how to work with it but it did linger in my mind. Then a big change for me came when I read Charles Bronson’s autobiography. About prison he says: “Maybe I always wanted to be there,” which intrigued me: that it’s not like other prison movies about somebody trying to get out, but about staying in. Then while I was preparing a Hollywood film that didn’t happen and trying to get VALHALLA RISING off the ground, a time slot opened up to work on BRONSON. And by this point I really did want to make BRONSON. I rewrote the script [which is credited to Brock Norman Brock and Refn] right before we were set to shoot. And then as I always shoot chronologically, I was able to reshoot about 30 per cent as we went along, when Tom Hardy, who plays Bronson, and I came up with new ideas. It very much progressed as we were shooting.

There are scenes of Bronson addressing a theatre audience with dramatic white stage make-up and also talking to camera. What was your intention there?

That’s an example of something I didn’t come up with until the final weeks of the shoot. I felt I needed to use that stage performance for something more than just an explanatory device. When I first looked at the project, there was more of a traditional voice-over in the vein of GOODFELLAS, in which the central character tries to justify his life to the audience. Instead, I came up with the idea that if BRONSON were a play, it would be a one-act monologue and by that I’d show that he was a man of many faces and that there’s no real Charles Bronson. BRONSON is not so much about Charles Bronson or even Michael Peterson, his real name, it’s more about the concept of becoming Charles Bronson.

You’ve said that it’s an allegory of your own life. In what way?

When I was young, I wanted to be very famous. In the film, Bronson does ultimately become a famous person, but he then realises it’s not that satisfying. It’s really when he opens himself up to artistic expression that he actually becomes a whole person and Charles Bronson is born. In fact, there are a lot of similarities with Hans Christian Andersen’s life. When Andersen was very young, he just wanted to become famous and he tried every kind of art form until he found what he was good at. Then he became a great artist and also very famous.

What contact did the filmmakers have with Bronson?

Tom Hardy had a lot of correspondence with Bronson, but I’ve never met him and only spoken to him once. He was very nice and wrote some thoughts on prison for me. He came up with a line that I put in the movie: “Prison is madness at its very best.”

You’ve made violent films. Where do you stand on the debate that violent films can lead to violence in real life?

I don’t believe that film makes people violent. However, because film is such a grotesque medium and so wide in its appeal, it can show how violent people react. It shows you how to be violent. As a filmmaker you have an obligation about what you do because a lot of people are going to see your work. Not that you have to censor yourself, but with great potential comes great responsibility.