Education and Participation – movieScope

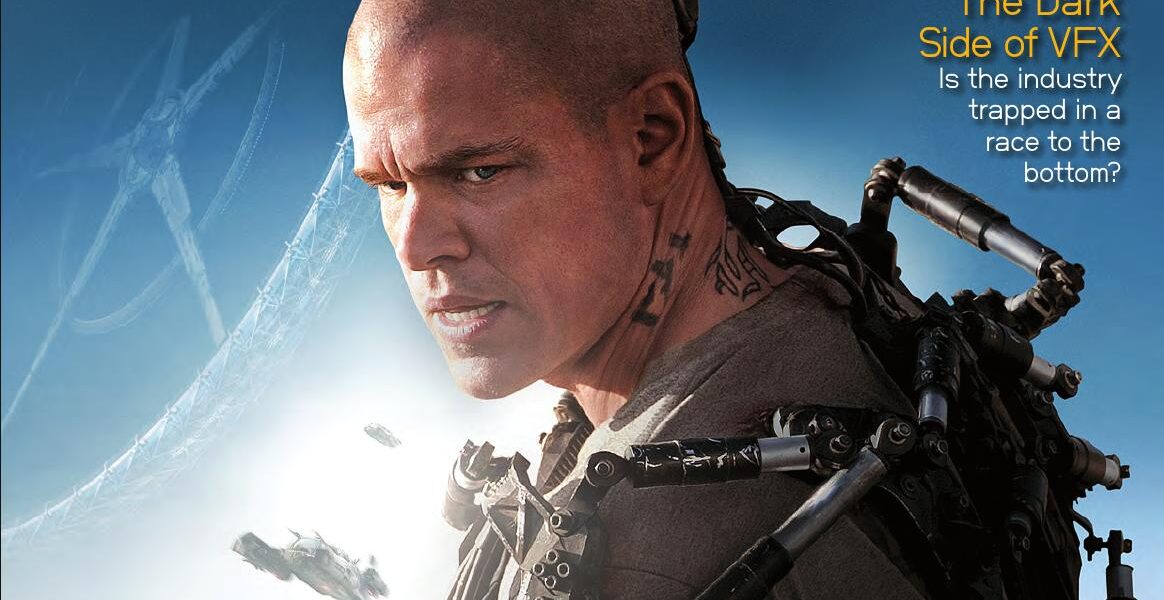

The Class, directed by Laurent Cantet

Industry analyst Michael Gubbins explores why any successful film education programme requires a much higher level of audience participation.

There is an understandable obsession in film about how it is possible to get young people to appreciate cinema. Every study shows that the audience for art-house and independent cinema is getting greyer, and the voices have become a little more insistent in recent years—perhaps, in part, because the percentage of youngsters as a proportion of the total population has been growing. In Germany, the average age of the population is now 43.7 but in 1970 it was just 34; in France, it is 39.7, compared to 32.5 four decades ago.

Perhaps the ageing process has exaggerated fears that have always been there, that youngsters will reject culture in favour of frivolous pursuits. Today’s discussions certainly have echoes of the scare around rock ‘n’ roll. The dramatic increase in choices of leisure activity, the strength of Hollywood franchises and a general fear that maturity no longer means putting away the childish pursuits of youth has been focusing the minds of policy-makers on how to refresh the roots of film culture. The biggest concern of all may be that the viewing habits of younger generations are changing in a way that fundamentally challenges the traditions of film.

Among the biggest concerns is that YouTube clips and multitasking—engaging in more than one media activity simultaneously—is drawing young minds away from the concentration needed to appreciate great cinematic art.

The European Union has recently commissioned a major report to study the way that young people consume film. But, more importantly, there has been renewed attention on film education. France has generally taken the lead in such initiatives, perhaps reflecting the unique importance of cinema in the shaping of national identity. The self-image of France and how it is seen abroad owes a great deal to the big screen; deep thinking, passionate, cool, etc. The image of the French abroad is similarly wrapped up in the moving image. There is a pantheon of French auteurs, whose work deserves critical appreciation, and of course an auteur theory to give an intellectual framework to cinema study. It is a serious political issue in a country which is built on a clear sense of the citizen within a unified republican culture.

Film education, then, is no small matter in France. Interestingly, a Palme d’Or winning film, Entre les murs (The Class), generated much debate about how far the multicultural French school was moving towards multiple identities and rejecting cultural values.

In the UK, there is less angst around this issue. Film has an important place in our culture, a fact documented rather well in a BFI-commissioned report entitled “Opening Our Eyes”. What that work shows is that there is a strong affection for film in Britain, if less sense of the importance of British film. The neglect of great historic work of British cinema would never have been tolerated in France. Interestingly, US director Martin Scorsese has been playing a key role in drawing attention to the importance of the UK’s own greats, such as Michael Powell, whose name would still mean little in the average classroom.

So far, film education has tended to be more about encouraging a love of film that it is hoped will translate into more cinema-going. The BFI is thankfully giving education a more serious look, and is currently considering tenders for a new education body, unifying a varied group of services. Hopefully, the result will be greater attention on understanding tomorrow’s audiences. It will perhaps play a role in a broader and more ambitious interpretation of film education, as also providing essential media-literacy skills that will be so important in terms of jobs and social mobility in an increasingly audiovisual economy.

But the weakest part of film education currently represents the biggest opportunity, and that is the unprecedented access to equipment for making and distributing film. Back in the 1960s, a bright young minister for information in the UK named Anthony Wedgwood Benn annoyed the establishment by suggesting that television and radio was destined to be the people’s medium: ‘Broadcasting is too important to be left to the broadcasters.’ The idea was more than just another piece of lefty Utopianism. Some of the pioneers of radio and television envisaged a two-way process of communication.

The democratisation of broadcasting never happened, however, for a number of reasons. One was indeed the vested interests of broadcasters. Lord Thompson, who won one of the first franchises for commercial independent television, famously called it a ‘licence to print money’. The more high-minded ideals of public broadcasting, in the UK and much of the world, spoke of a top-down mission—in the case of the BBC, the founder Lord Reith described its duty as to ‘educate, entertain and inform’. Between these two competing visions, television became something that, to a greater or lesser extent, was for the people, but quite deliberately not from the people.

Film was never seen in those terms. The cost of the raw materials, the limited ways of screening film, and the growth of specialist skills mean that film was necessarily something created by professionals for an audience. It was never the people’s tool, even if it has sometimes been the greatest medium of popular sentiment.

The digital age has changed that relationship between content creator and producer and audience. We could now realistically live out Benn’s sixties dream; we could all now be broadcasters, and perhaps social networks, YouTube, etc., means we already are. Of course, the Internet is a gargantuan demonstration of how democratisation creates vast quantities of content and a tiny proportion of quality. But in a sense that does not matter. People who pick up musical instruments as children normally abandon them when they realise that tickling the ivories or scratching with a horse-hair bow will never reach professional levels. On the other hand, research shows that even a rudimentary understanding of how an instrument is played can lead to a lifetime’s appreciation of great music. Filmmaking may be too important to film culture to leave to the filmmakers.