Has Veronica Mars changed Crowdfunding Forever?

With the Veronica Mars movie project breaking all Kickstarter donation records, many are proclaiming that the face of crowdfunding has been forever changed. Nikki Baughan examines just what impact the project’s success will have on grassroots filmmakers who have made crowdfunding their own.

This article first appeared in movieScope 34, (May/June 2013)

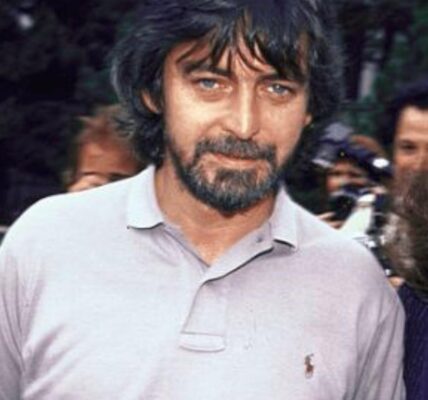

At the time of writing, Rob Thomas’ much publicised Veronica Mars Kickstarter project has just closed. After smashing its $2m goal in 10 hours, it went on to amass over $5.7m in financial contributions over the course of just one month; an astonishing 91,585 people from over 20 countries backed the project, breaking several Kickstarter records in the process. Most of those pledging money fell into the smaller $1–$100 categories but there were individuals who donated thousands.

While Veronica Mars may be the most high-profile project to have turned to crowdfunding, Rob Thomas and his team are certainly not the first established filmmakers to have sought funding in this way. Celebrated screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (Being John Malkovich, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind) launched a Kickstarter campaign in September 2012 for his stop- motion animation Anomalisa. It raised over double its goal of $200k. And, just as we went to press, filmmaker Zach Braff (Garden State), announced that he had launched a Kickstarter funding page for his new film Wish I Was Here, with the hopes of raising $2m-and was well on his way to smashing that total.

It’s clear then, that while crowdfunding may have once been the bastion of grassroots, super-low-budget filmmakers who struggled to access traditional funding models, increasingly bigger projects are now reaching directly to their potential audiences to secure their budgets. It’s fair to say that they have good reasons for doing so; Thomas had been trying unsuccessfully to convince Warner Bros.— who own the rights to Veronica Mars—to make a movie for years, for example, while Kaufman is adamant that Anomalisa can only thrive outside of the studio system. And somewhat ironically, but entirely unsurprisingly, the willingness of backers to put hands in pockets seems to increase the more well known the project or filmmaker; perhaps the benefits of having a helmer with experience or the desire to be part of a community of fans who are—as Thomas and star Kristen Bell kept reminding Veronica Mars funders—literally coming together to save the day.

While the fans may have come out in force to support Thomas, Kaufman and Braff, reaction to these potentially game-changing projects has been mixed, with Twitter proving the usual hotbed of debate and dissension. Critic James Rocchi actively discouraged his 8,000- plus followers from supporting the Veronica Mars project, calling it “food stamps for the one per cent”, while writer/director Joe Swanberg (V/H/S, Drinking Buddies) questioned the fiscal logic behind the whole endeavour. “So WB just put themselves out of business,” he tweeted. “If the audience can pay to create the movies they want, we don’t need studios anymore, right?”

Of course, these 140-character-or-less commentaries don’t tell the whole story. Drill a bit deeper into the success of Veronica Mars and it becomes less a story about crowdfunding and more about the effectiveness of good branding. The project had the benefit of a large and devoted fan base, built up over the show’s three years and 64 episodes, which was vocal in its continued support even after it was taken off the air in 2007. It also possessed a major asset in recognisable lead actress Kristen Bell, who was extremely proactive during the campaign. The majority of donors were undoubtedly existing fans of either the show or its star, so effectively the groundwork had already been done; the opening of the financial floodgates was the final—and self-proclaimed ‘last-ditch’—stage of a long and rocky process for Thomas.

That said, the crowdfunding response to Veronica Mars undoubtedly surpassed all expectations, and Warner Bros. will certainly be taking a closer look at how they can involve potential audiences in the gestation of future projects. “Warner Bros. [is] treating us like a guinea pig, in the best way,” Thomas said in an interview with HitFix. “They want to see if this model works and they made the calculated decision… that we were a good test case for this. We just happened to be the right show at the right time, got to be the first one out of the gate.

If it works, it works, and [Warner Bros.] could start doing more of these. And you know that if it works at one studio, that they’re not going to be the only studio in town that will be trying it.” Similarly, other content producers have expressed an interest in the model. TV creator Shawn Ryan intimated that crowdfunding may be a way for him to breathe new life into his cancelled show Terriers, tweeting that he is “very interested to see how this Veronica Mars Kickstarter goes. Could be a model for a Terriers wrap up film”.

It seems, then, that crowdfunding may be poised to become an additional revenue stream for bigger projects, studio and independent alike. But what does that mean for those low-budget, unknown filmmakers who rely entirely on crowdfunding donations to get their projects off the ground? If studios elbow their way into Kickstarter or Indiegogo or Sponsume, will that mean less money for those at grassroots level? Thomas certainly doesn’t think so. “I think what Veronica Mars has done is brought Kickstarter to the masses,” he said in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter. “More people are now familiar with Kickstarter, and more people are browsing Kickstarter for other projects, [who] now understand what it is and what it does than before we launched our campaign. I think we’re bringing more eyes to that site, so I think that has to be good for indie filmmakers.”

Somewhat surprisingly, perhaps, this opinion is also shared by independent filmmaker Sarah George, who has successfully run several Kickstarter campaigns and is a member of D-Word.com, an online discussion forum for documentary professionals.

“In my opinion, the only downside is if it starts to feel exploitative; corporations making insane money from the goodwill of crowdfunders without returning any benefits,” George says of the concept of sharing Kickstarter space with major players. “But I believe that people know the difference.

“I don’t look at the crowdfunding landscape from a perspective of scarcity,” she continues. “I think there’s enough enthusiasm to go around, and I think that enthusiasm is very project- specific. I’m actually very curious to see what happens with equity crowdfunding, because I think that could be a huge game- changer for commercially viable projects. But, I do think that incentive-based crowdfunding is here to stay, and will continue to be a sustainable source of funding for independent artists and a rewarding experience for their backers.”

Indeed, George believes that this renewed interest in—and publicity surrounding— crowdfunding can only be of benefit to all creatives who are invested in their projects, and that the motivations of both content creators and their supporters will remain fundamentally unchanged.

“I think we are still in the early days of crowdfunding, and I believe it’s here to stay,” she asserts. “I expect to see a surge in creative output precisely because everyday people now have the opportunity to commission work that speaks to them. My sense is that in an increasingly fragmented media landscape, we may come to see the work we fund as an individual expression of personality and taste. Rather than tune into a network as an aggregator of content that serves a particular dynamic, we may be more inclined to become curators of our own personal media art collections that we are happy to pay the artists directly to create. The best part of crowdfunding is that it is a two-way street. The future audience is excited to bring an artwork to fruition, and the artist is eager to embrace a community of support.”

George raises an important point, that, despite recent high-profile successes and potential studio involvement, crowdfunding is likely to remain the domain of the small, targeted project rather than the common- denominator blockbuster. In terms of budgets, Veronica Mars’ $2m ask is comparatively very small, as is the $5.7m they raised; it’s almost impossible to imagine a Kickstarter project bringing in anything close to the $100m-plus that the likes of Oblivion and Iron Man 3 chew through. Any project that big will have studio support, mitigating the need for the public to stump up their hard-earned until they queue up at the box office.

Thomas himself understands that crowdfunding won’t be right for every project, stating in an interview with Wired that their success “will be an important pioneer for a certain type of film. I’m not convinced that this will revolutionise how most movies get made, but I think there’s an opportunity now for projects that are similar to ours—that have some public support before they launch on Kickstarter. “With this model, it’s almost a marketing device, a way to judge if there was enough interest in a movie this size,” Thomas continued. “For a Friday Night Lights movie or a Freaks and Geek movie or a Chuck movie, I think it could be a possibility. I think this opens up a door. What I’m interested in as a writer is [if] a writer optioned a book and brought on an actor with some name value—if that combination could raise the money on Kickstarter to make a movie.”

Thomas’ project may have been a successful marketing tool, but it does remain to be seen just how much of the donations received will translate into the film’s budget, despite Thomas’ assertions that 100 per cent of the fans’ money will go into making the film.

“It’s all going to the budget of the movie,” he told Wired. “The back end of the movie is divvied up like any other movie that gets made. The stars of the show will get a piece of the back end; the producer will get a piece of the back end. Clearly Warner Bros. will own a big part of it. I think there’s a scenario where everybody wins; where Kristen and I get to make the move we’ve been hoping to make, where fans get to see the movie and where Warner Bros makes money on it as well.”

While the optimism that surrounds this project is palpable, no real mention has been made of the cost of the ‘perks’ that have been purchased by funders. Everything from posters to T-shirts, and DVDs to autographed pictures will need to be manufactured and shipped around the world, and fans will need to be accommodated at various premieres—not insubstantial costs. (Other perks, including being followed on Twitter by Kristen Bell, answer phone messages recorded by the cast, naming a character in the movie and appearing as an extra in the film have less of a fiscal impact.) Only time will tell who foots the bill for the fulfilment of these incentives—and, indeed, whether those funders who will be receiving digital or physical copies of the film will be prepared to pay again at the box office.

Of course, not all filmmakers who turn to crowdfunding can afford such a wide range of perks—and many have come unstuck when trying to fulfil funder demand—but, as George explains, running a successful crowdfunding project goes way beyond merchandise.

“I think the biggest risk is to not ask for enough money to do justice to your film and story,” she says. “Your backers expect you will deliver what you say you will. Make sure you ask for what you really need—and then it’s your job to explain why you need what you need. I think that’s particularly true for filmmakers because so many people are shocked to learn what it really costs to make and finish an independent film. I think it’s crucial to understand from the beginning that you are entering into a relationship with your backers. It’s pretty simple, really: treat them the way you’d like to be treated!

“I just completed a Kickstarter campaign which raised $12,497 to make a short documentary called Dwayne’s Photo,” George continues of her own experiences, “about Dwayne Steinle and his family-run photo lab in Parsons, Kansas, that’s become the last place on earth to process Kodachrome. My campaign was fairly modest, but of course I was still nervous! I can’t say for sure why it was successful, but it really mattered to me that I conduct the campaign with integrity. I wanted everyone who participated to feel good about it. I started by putting together what I thought were some very cool incentives; I was genuinely excited about the rewards and that meant it was easier for me to invite people to participate. I also make an effort to include the makers of the rewards in the campaign. Like a good old-fashioned 12-step programme, it helped to take one day at a time. I constantly created short-term goals that I was fairly confident I could achieve.

“For most of us, it isn’t easy to ask family, friends and complete strangers for money. Much easier to ask people to participate in something you are passionate about! I used my campaign updates and social media feeds to engage people by crafting a narrative and sharing my reasons for making the film. Focusing on the story also served as reminder to myself of why I was doing it.

At one point in the campaign I was struck by the ‘Zen’ of crowdfunding. I realised that it requires the practice of letting go, of control, ego and outcome. You just have to focus on enjoying the ride, the people you connect with, the things you discover, and trust that somehow it will all work out. If you believe in your story, and you know you have an audience, then it is very empowering to reach out and engage them directly. Crowdfunding also taps into the phenomenon of the kindness of strangers, and it’s true that it is an antidote to the accumulated cynicism of everyday life. It reminds us of our shared humanity.” •

Taken from movieScope magazine, Issue 34 (May/June 2013)