A survey from the European Audiovisual Observatory suggests that there are now more than 500 video- on-demand services available in the EU dedicated mainly or wholly to feature film. And, despite a small dip in 2012 (due to a fall in documentary production), the EU countries’ production of nearly 1,300 films a year represents a 75 per cent increase in output over the last decade.

This all sounds like great news for the consumer and, to the outsider, it might seem that subsidised and protected film production in Europe is in rude health. Yet there’s a persistent paradox that will not go away; let’s call it the illusion of choice. While all of the experimentation in new platforms and release windows has unquestionably increased the volume of films available, volume and choice are not the same things. A mathematician might have a lot of fun working out the number at which human beings might make a genuine choice of alternatives. Columbia Business School Professor Sheena Iyengar offered a fascinating insight in a TED talk earlier this year, showing that consumers were more likely to buy from a selection of six items (in that case, pots of jam), than of 24. For independent filmmakers and the organisations and bodies tasked with building diversity of content, however, these are not academic issues.

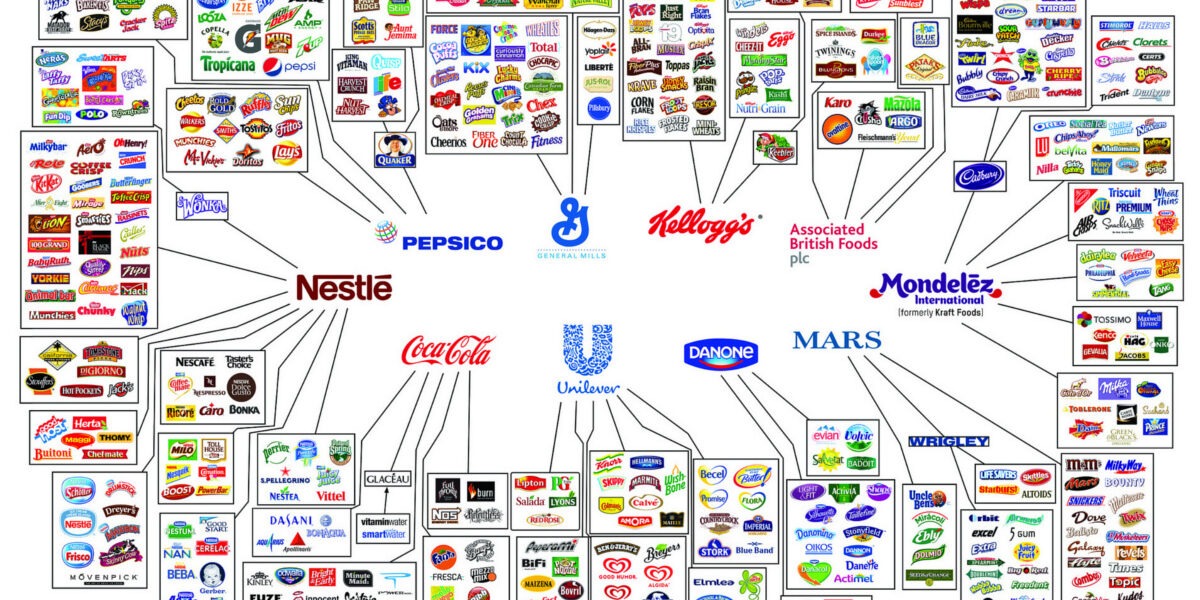

In fact, there are two issues at stake here. The first is the big question of how you build business models on practically unlimited choice but limited consumer time. The multinational media platforms and globalised retailers are finding their way around this problem by mobilising big data, to curate—some would say manipulate—consumer taste. Amazon, for example, has what seems like an uncanny knack of predicting taste but its success is built on mining rich and vast fields of audience data, which are added to with every interaction. What’s more, consumers willingly help that process by volunteering additional information in the hope of personalised services. (Oddly, the power that this gives multinational giants does not seem to create the same adverse public reaction as to governments monitoring and collecting information on citizens.)

That level of data access does not scale down, but smart independents are finding ways of aggregating demand. Crowdfunding is perhaps the most benign form of the process, with a few key branded sites, such as Kickstarter, helping bring together like- minded people to support a project in which they feel they have a stake. We are then in a world in which it is possible, at least to some extent, to engage audiences with known tastes. There is a lot of self-serving nonsense spoken about how the growing potential to service existing audience demand is compromising to art. This is not just an issue of slavishly following market trends. Instead, it is about ensuring the broadest audience for content, and that is just as important to any cultural mission worth the name as it is to commercial imperatives.

That brings us to the second serious issue. It may be increasingly possible to accurately and dynamically service audience tastes; Internet business is profoundly focused on personal gratification. But how do you create taste and demand in the first place? It may be considerably easier to give people what they think they want, but how do you awaken passion that they do not know they have?

Ironically, many of today’s more adventurous lovers of film were introduced to it because of the limited choice of options, particularly on terrestrial television. It is fashionable now to talk in disparaging terms of the evils of ‘gatekeepers’ between content and audience. Yet the public broadcasting mission, summed up by the founder of the BBC, Lord Reith, as the need to ‘educate, inform and entertain’, did at least ensure exposure to different forms of art and culture.

It was a patrician culture, of course, which put huge amounts of power in the hands of a small state elite. The relationship between the broadcasters and the law-makers was dangerously close and, in some states, profoundly undemocratic and deferential. But the on-demand culture of the Internet era has not yet found effective means of ensuring that choice is an educated selection between a considered variety of options rather than the product of market forces. Unlimited access to content has tended so far to polarise demand around the pervasive marketing mainstream and smaller, narrower, local or niche tastes.

Hollywood’s strategy of the last few years necessarily exacerbated these trends. The studios have been betting their future on fewer but bigger films, having largely divested themselves of the specialist production arms. At the turn of the century, there were four films made with budgets above $100m. Last year there were 22. To recoup on that level of investment requires ever-greater domination and marketing strategies that squeeze out alternatives.

In June, Steven Spielberg warned that the reliance on globally marketed movie behemoths risked the long- term implosion of the industry. One could also make a strong case that Hollywood needs a diversity of content to keep cinema’s central place in national cultures worldwide. But the polarisation in which big films get bigger and small films get invisible is also true in Europe.

EAO’s annual Focus Report also reveals that the top two per cent of EU-produced films made up almost half of the total 328m admissions for EU films last year. In fact, the top film, Skyfall (below, categorised as UK-US by EAO) made up 13.5 per cent of the total. The latest in the James Bond franchise was almost single-handedly responsible for the increase in European market share in 2012. Again, unlimited choice tends to favour the biggest and loudest.

For the individual producer, it is becoming essential to think harder about the target audience, and how to build the necessary levels of awareness and engagement at a much earlier stage. There is, however, a bigger issue that should now be at the heart of public policy. How do we ensure that film culture does not fragment into a variety of exclusive fan bases and taste groups? And how do we ensure the broad access to film that will be at the heart of future demand? •