Costume design remains one of the most misunderstood and under-appreciated filmmaking arts. Far in excess of merely dressing an actor for their role, costume design is discourse.

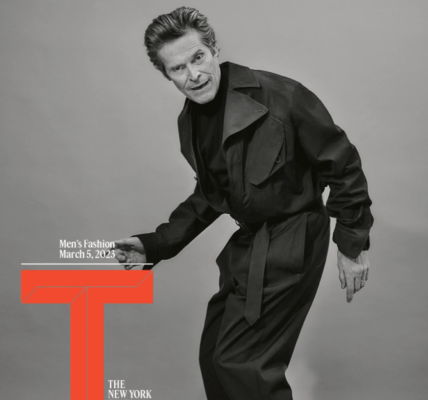

A film can be read via costume, sometimes overtly, other times by subtext. This applies to not just conspicuous sci-fi or period pieces, but also contemporary stories set within a familiar world in familiar attire. On screen, even the most rudimentary item of clothing can take on meaning. A white T-shirt on film is never just a white T-shirt: consider Brando, Dean or Delon. When viewed in context, it is the ultimate symbol of male sexuality. Quite simply, it is costume nakedness. Vulnerable, pure, masculine; a plain white shirt is the most erotic force in cinema.

2010 was a boundary-crossing year for costume. Beyond the typical crop of historical dramas, fantasy and comic book adaptations, all of which are commonly accepted as highly visible and emblematic forms of sartorial expression, the past 12 months have seen a number of contemporary films garner attention for their clothing. Inception would be a prominent example. Although science fiction to a degree, the story exists within a recognisable world, with costume designer Jeffrey Kurland creating, literally from scratch, a stylish and functional template for differentiating character, and even for interpreting plot. There are subtleties within the film that allude to time, space and the emotional make-up of the protagonists: Eames (Tom Hardy), the relaxed, travelled member of the group wearing tropical style splayed collars and a linen jacket; Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio), dark and unsettled, his clothing loose and layered in a sombre colour scheme; Ariadne (Ellen Page), creative and young, a typical Paris student in a patterned silk scarf; and Arthur, signature in a three-piece suit, measured and fastidious. This applies to the minor characters too, such as Cobb’s mentor Miles (Michael Caine), his Nehru collar shirt and tweed jacket suggesting the familiar look of the academic, while projecting a futuristic, even dreamlike, air. That such a simple costume touch could imprint on the narrative is not too great a leap. Consider what Cobb’s children are wearing at the end of the story. On first glance this is the same as within his flashbacks, yet look again and their clothes reveal a different, potentially momentous truth.

Costume design need not be subtle. Particularly in science fiction, clothing is often used as visual iconography that speaks to the audience, though without breaking the fourth wall. When a world is unfamiliar or at the behest of its own rules and backstory, dress can fill in the blanks, as it were. Tron: Legacy applies costume, specifically light and colour, as shorthand to establish factions within its near monochrome ‘grid’. The story’s antagonists display yellow and red, loyal to master program CLU in orange. Those apathetic or against CLU wear white and blue, and during a brief though vital turning point, a principal character changes their allegiance from red to white.

These are meticulously applied principles by director Joseph Kosinski and costume designers Michael Wilkinson and Christine Bieselin Clark. They cannot be broken, for risk of undermining Tron’s fabricated reality. Moreover, further rules apply in regards to the type of material worn inside the Grid: only latex foam and spandex, never organic fibres such as cotton jersey. Watch closely as the character Sam Flynn (Garrett Hedlund) transfers from bio world to Grid; his sweater hood is casually blown inside the collar of his jacket, effectively hiding it from the audience and preserving the film’s costume laws.

Communication via costume can be employed to break the fourth wall, even if this device remains largely the preserve of avant-garde or anti-plot films. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, though intrinsically a comic book adaptation, plays with many forms of narrative interpretation. The seven evil exes, Scott’s conflict throughout the story, all bear a hidden number to denote their position within the villains’ hierarchy. An obvious example is Lucas Lee (Chris Evans), ex number two, who has two Xs embossed on his belt. This is a message for the audience; clues are there, should we wish to partake, yet are not prerequisite for following the plot. Just another way that costume can enrich our viewing experience by reaching out and gently tapping us on the shoulder.

Of course there is a more traditional role for costume, in that clothes worn can encompass an entire genre. The ‘costume film’ is saddled with the responsibility of satisfying an audience based purely on the protagonists appearing historically accurate and/or alluring. Yet the costume film does not exist. There are period dramas, comedies and love stories, but costume enhances, rather than defines, their narrative. Period costume is alive with symbolism, the covering and exposing of flesh, layers of undergarments, sheer fabrics and the rebelliousness of flouting the rigid formalities of dress code.

Robin Hood was one of the more interesting period films of 2010. As a biopic it strived for realism while retaining the basic costume profile of its folk hero, i.e., a late medieval, typically short tunic, though no woodsman hat and feather. Director Ridley Scott and costume designer Janty Yates applied their craft within an interpreted rather than exaggerated reality. Clothes worn during this period were simple and class dependent, either for display or climate. Prince John (Oscar Isaac) sashayed in a flowing silk robe while Robin (Russell Crowe) crouched, cold and damp, in woollen hose.

Accuracy is not only important in period productions. The Social Network, set within a historical framework though not ‘period’ in the customary sense, featured detailed recreations of outfits worn by the story’s real-life protagonist, Mark Zuckerberg. A man widely acknowledged for his refusal to conform to fashion, Zuckerberg was apparently satisfied with this portrayal in the movie by actor Jesse Eisenberg; the black North Face fleece and Adidas flip-flops encapsulate his radical silhouette. Most fascinating, however, is a rudimentary Gap sweater that was actually remade by costume designer Jacqueline West so that the logo could be read the correct way round in a reflection. Even a sweater is never just a sweater on film; it is a powerful creative tool. Interpretable and evocative, costume has stories to tell and secrets to spill.