The Role of the Stereographer – Cinema’s newest profession – movieScope

Home » Featured » The Role of the Stereographer – Cinema’s newest profession

Page Contents

The Role of the Stereographer – Cinema’s newest profession

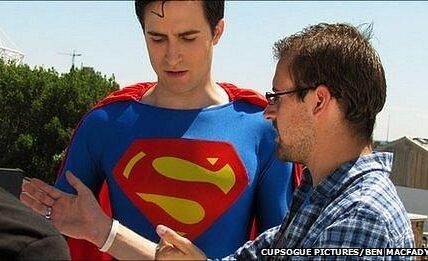

Stereographer Chris Parks takes us behind the scenes of his craft and explains why, with 3D becoming a staple of modern cinema, his role is becoming essential to successful filmmaking.

The recent barrage of 3D films has brought with it a tide of ire from various sides, with opponents keen to dismiss it as a passing fad, a tool used merely to extract a higher ticket fee from the pockets of enthusiastic cinemagoers. Its supporters, however, claim that the potential of 3D has yet to be fully explored, and that its ability to affect audiences emotionally makes it as important to the evolution of cinema as colour was early last century.

Working tirelessly behind the scenes as this war rages on, Chris Parks has brought his 17 years of experience as an architect of 3D to cinema’s newest profession: the stereographer. Starting out developing 3D for books and museums, Chris Parks experimented with using it on the big screen while shooting nature documentaries for IMAX and designing his own lenses and rigs. He is now one of the most sought-after stereographers, his recent projects including Pirates Of The Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, Clash Of The Titans 2 and Jack the Giant Killer. MovieScope met up with Parks at his home in London, to discuss the increasing importance of the stereographer, and the full power of 3D filmmaking.

So what specifically does a stereographer do?

The role of a stereographer hasn’t really been fully described. I’ve never been trained to be a stereographer, because there’s nobody who’s done it before. If I’m involved on a project, I’m basically responsible for the 3D. That involves specifying the equipment, discussing cameras and lenses with DPs, working out what the DP wants to do in terms of the look of the film, making sure the 3D gear is consistent with that and will ensure that he is able to achieve the look of the film that he wants.

How do you approach 3D filmmaking?

3D is much more about the space between objects than it is the objects themselves. A single object like a snooker ball is a very round clean shape and doesn’t actually give you very good 3D itself. Take a bunch of snooker balls, define a volume and suddenly that gives you much more pleasing, interesting 3D. With a single snooker ball, the two camera views for the two eyes are almost identical, apart from maybe a change in position on the specular highlight. That’s the same whether you’re post-converting or whether you’re shooting native 3D.

Is most of your work done in pre-production?

Yes, often before the DP’s been assigned. In pre-production I’m trying to work with the director and the DP and the designers and even the make-up to ensure that the decisions they are taking will help the 3D, and ensure the 3D is going to help the director tell a story. So, by the time you get to shooting, everybody knows what they’re trying to achieve, everybody’s on board with the process and they know the sorts of things I’m considering.

Do you have a version of a storyboard for planning the 3D?

I produce what’s called a ‘depth script’ from the script and storyboard. I use it to solidify my own ideas as to how I’m going to use the 3D, where I’m going to have the 3D strong, where I’m going to allow the audience to relax, where I want stuff to come out or stay behind the screen. It becomes a discussion document, something I can talk to DPs and directors about, and it gives them a visual sense of what the 3D’s going to look and feel like. They might want to be poked in the eye with a sword or draw an audience into a scene or test the audience. They may want lots of depth on a close-up and then move into a wide shot and want to know how to get from one to the other.

What does a depth script look like?

The ones that I put together typically plot scenes or the shot number on the script against the 3D. I’ll plot a line for background, foreground, key objects, and the main focus of the shot. I might do that for a scene, but then I might break down a scene into individual shots. I’m trying to have a flow and narrative to the 3D, so it supports the story and the pace of the film. In order to do that, you need to plan it out.

When you talk about testing or drawing in an audience, what do you mean in terms of 3D?

I’m interested in how you can use 3D to help tell a story. For me, if an audience comes out of the cinema going, ‘Wow that was fantastic 3D’, then I’ve failed; that’s not what 3D is about. I want somebody to come out of the 3D film having laughed more than if they’d come out of the 2D version, cried more, having empathised more with the characters, having understood the message—I guess being affected more subconsciously, whether it’s the emotions or the beauty or the claustrophobia. I’m always looking to use the 3D to do something more than just add depth in a project.

Specifically then, how could 3D be manipulated to cause a feeling of, say, claustrophobia?

On a very simple level, you could pull the perceived plain of the screen up to the audience so they feel they’re closer to it, you could feel like the back wall of the room that the character is in is up closer to the audience, in front of the screen so the whole scene exists in front of the screen. Or you can push it away so it feels it’s out there in the distance and unreachable and full of space. And that’s what 3D really can do and doesn’t typically get used for.

Have blockbusters like Avatar been a positive step for the public acceptance of 3D?

Avatar was a landmark 3D production, whether you like it or not. The big question was whether you can have a three-hour film in 3D that is watchable. What it achieved was, say, here’s a three-hour film in 3D that won’t give you a headache. It certainly didn’t detract anything from the story; you could question how much it added to the story, and that’s where we have to move forwards with 3D. It’s not just stereographers who have to learn, it’s the directors and the DPs and the designers. The more they start trying and experimenting within their roles of how 3D is used and adds to the film, the better. •

Taken from movieScope magazine, Issue 23 (July/August 2011) – ON SALE NOW

Taken from movieScope magazine, Issue 23 (July/August 2011) – ON SALE NOW